On 6 August 2015, the American author and playwright James Purdy left New York for the last time. Bound for Denmark, he travelled in a small flip-top leather case with a combination lock. This was inside the rucksack of Maria Cecilia Holt, Harvard doctor of theology, who was asked to produce the necessary papers while going through security at Boston Logan airport.

“I’d collected James’s ashes from his literary executor,” she explains. “It had been quite traumatic. So I presented security with the papers and the ashes and they said, ‘Ma’am, we’re sorry for your loss.’ I began to cry. I wanted to say, ‘It’s not my loss, it’s yours. America is losing a great writer. He’s leaving the US for ever – and no one even cares.’”

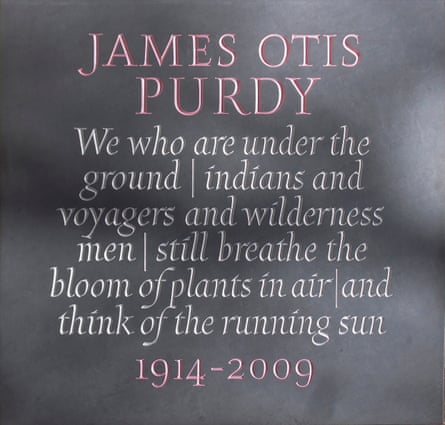

Holt gave the ashes to Charles Lock, professor of English literature at Copenhagen University, who put them on his bookshelf – and that’s where they have been for three-and-a-half years. However, on 13 March, exactly 10 years after Purdy’s death at the age of 94, Lock will travel with the remains to the graveyard of St Mary’s Church in Weedon Lois, Northamptonshire, where they will be interred next to the grave of the English poet Edith Sitwell, in accord with Purdy’s final request.

“The idea was appealing in its sheer oddness,” says Lock, who was asked to help by Purdy’s literary executor. “I don’t think there’s another American writer of such importance buried in Britain. TS Eliot, of course, but he’d long been a British subject.”

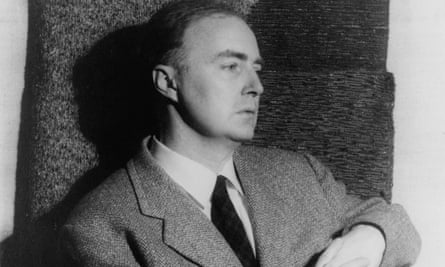

When Purdy died, obituaries eulogised him as a unique, fearless voice of American fiction. They praised his bizarre, savage wit, his dreamlike vernacular prose and its ability to conjure up gothic midwestern landscapes of beguiled innocence, grotesque violence and gender-fluid racial and sexual obsession. But they also pointed out that this white, midwestern writer who wrote about outsiders – women, African Americans, gay people, Native Americans – was himself cast out by the US literary establishment.

Despite praise in his lifetime from Langston Hughes, Susan Sontag, Edward Albee, Gore Vidal, as well as – in later years – John Waters and Jonathan Franzen, Purdy felt more loved in Britain. He talked often of how the critic and poet John Cowper Powys called him “the best kind of original genius” – and of how Sitwell helped him publish 63: Dream Palace, his first novella, in 1957. He eventually notched up a total of 18 novels and 20 plays, as well as numerous poems and short stories.

“English critics saw something unique in Purdy,” says Professor Richard Canning, a Purdy scholar at the University of Northampton, who has organised a symposium on the writer’s work to follow the burial ceremony this week. “Purdy met his American critical neglect with incomprehension, suspicion and anger. Yet from the start, he could write no other way.”

The writer was born poor in Hicksville, Ohio, in 1914. His parents divorced when he was young, so Purdy moved between his mother and father, and his grandparents, who would tell him strange gothic tales that he’d transform into short stories and plays, utilising the language of the King James Bible and Shakespeare’s dramas, works he was made to read cover-to-cover by his Calvinist family. “I think it taught me the English language,” said Purdy. “I grew up in a family of matriarchs. They were all inveterate storytellers.”

Purdy studied English at the University of Chicago where, in 1935, broke and without friends, he befriended Gertrude Abercrombie, painter and “queen of the bohemian artists”, whose ruined mansion was a popular stopover for jazz artists including Sonny Rollins, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, and Billie Holiday. Inspired by the improvised jam sessions at Abercrombie’s salon, and by the writers of the Harlem renaissance, Purdy developed his unique writing style, incorporating a small-town midwest vernacular and African American slang.

“Jazz is a good description of Purdy’s writing,” says his biographer, Michael Snyder. “He incorporates different tonalities and voices within a single story, employing this archaic, almost biblical American language.”

Purdy began sending out his stories to magazines. But, as he wrote in An Autobiographical Sketch in 1984, they “were always returned with angry, peevish, rejections … They said that I wrote in a peculiar manner … too vivid. [They] were insistent I’d never be published.”

If it wasn’t for Sitwell, that might have been true. But in the period following Gollancz’s publication of 63: Dream Palace, with Purdy ensconced in a small apartment in Brooklyn Heights, his work was briefly in vogue. His first novel Malcolm, an absurdist Candide-like journey through an American metropolis, was described by Dorothy Parker as “the most prodigiously funny book [of] these heavy-hanging times”, while 1961’s follow-up, The Nephew, was hailed by Angus Wilson as “a reverberating work [of] magnificent simplicity”.

Feted by the establishment, Purdy received a Guggenheim Fellowship, and an award from the National Institute of Arts and Letters. But just a few years later, he bit the hand that fed him (clean off, you could say) with Cabot Wright Begins. A scabrous satire about three of New York’s sacred cows – publishing, politics and psychiatry – the novel concerns the battle for the biographical rights of the titular Wright, a handsome, Yale-educated stockbroker and serial rapist. New York Times book critic Orville Prescott called it “the sick outpouring of a confused, adolescent, distraught mind”. A counter-attack from Susan Sontag hailed it as “a bravura work of satire”, but the damage was done.

“If my life up to then had been a series of pitched battles,” wrote Purdy, “the future was to be a kind of endless open warfare.” Cabot Wright Begins, he added, “was condescendingly reviewed by the pew-warmers of the local think tanks. [It] was not about a rapist but about people that try to write a book about a rapist. It’s about writing. Nearly everybody missed that.”

However, it was Purdy’s next novel, Eustace Chisholm and the Works, that especially outraged the “pew-warmers”. A violent hallucinatory work set in Depression-era Chicago, it told the story of a Native American who can’t accept he’s in love with another man. The book, said Purdy, was about how “we rip out the beautiful things in us so we’ll be acceptable to society”. Dismissed by the New York Times as “a homosexual novel”, the book was also denounced by the writer Nelson Algren as a “fifth-rate avant-garde soap opera [about] prayer and faggotry”.

Despite it being his bestselling book, with a review in the Sunday Times by George Steiner praising its “power to make nerve and bone speak”, Purdy was effectively marginalised for the rest of his life. “My books are all underground,” Purdy told Interview magazine in 1972. “They’re about something people don’t want to hear expressed. Critics would like to carry them off to the shit-yard, [but] they can’t, because they haunt people.”

“He was tapping into something deep within us,” says biographer Snyder. “He was writing about same-sex love and desire, saying it could happen to anyone. Plus, he was combining that with issues of race and power. New York critics just shut him down and diminished his name.”

The label “homosexual writer” stuck for the rest of his career, with Purdy confined to what Gore Vidal called “the large cemetery of gay literature … where unalike writers are thrown together in a lot, well off the beaten track of family values”. In later years, Purdy moved further off the beaten track, as much by intention as circumstance. “I’m not a gay writer,” he would tell interviewers. “I’m a monster. Gay writers are too conservative.”

Speaking to Penthouse magazine in 1978, Purdy said being published was like “throwing a party for friends and all these coarse wicked people come instead, and break the furniture and vomit all over the house”. He added that, in order to protect oneself, “a writer needs to be completely unavailable”.

“The public image was something horrific to him,” says Purdy scholar Canning. “But he was also completely impossible. He refused to play the game. When Derek Jarman wanted to make a film of his 1976 novella, Narrow Rooms, Purdy asked who Jarman wanted for the lead, then said, ‘Over my dead body!’ For the rest of his life, Purdy regarded Jarman as the biggest traitor. When I interviewed him in 1997 a lot of what he said was slanderous, or unintentionally offensive, or settling scores … though it was also pretty funny. He was nobody’s servant.”

In the last 10 years of his life, Purdy also developed a circle of acolytes not best interested in promoting his reputation. “They believed in alchemy and secret genealogies,” says Canning. “You’d call his apartment and other people would answer the phone, saying he wasn’t in. People were worried about him, but he always loved being on the wrong side of the tracks.”

“He put his worst foot forward,” says Snyder. “But because he remained uncompromising, his style still feels fresh, weird and unique. His 1989 novel, Garments the Living Wear and his final short story, Adeline, were both ahead of their time in dealing with gender fluidity.” Then there’s Cabot Wright Begins, the book that destroyed Purdy’s career. Snyder insists its time has come. “It has all the hyperbole and hysteria of Trump’s America,” he says. “Purdy got under the skin of America to something deep, universal and macabre.”

What Purdy would think of the burial ceremony, and this revival of interest in his work, remains debatable. “I don’t think I’d like it if people liked me,” he once remarked. “I’d think something had gone wrong.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion