Ana Matronic on seeking justice and Scissor Sisters’ return: ‘You can never fully close the door’

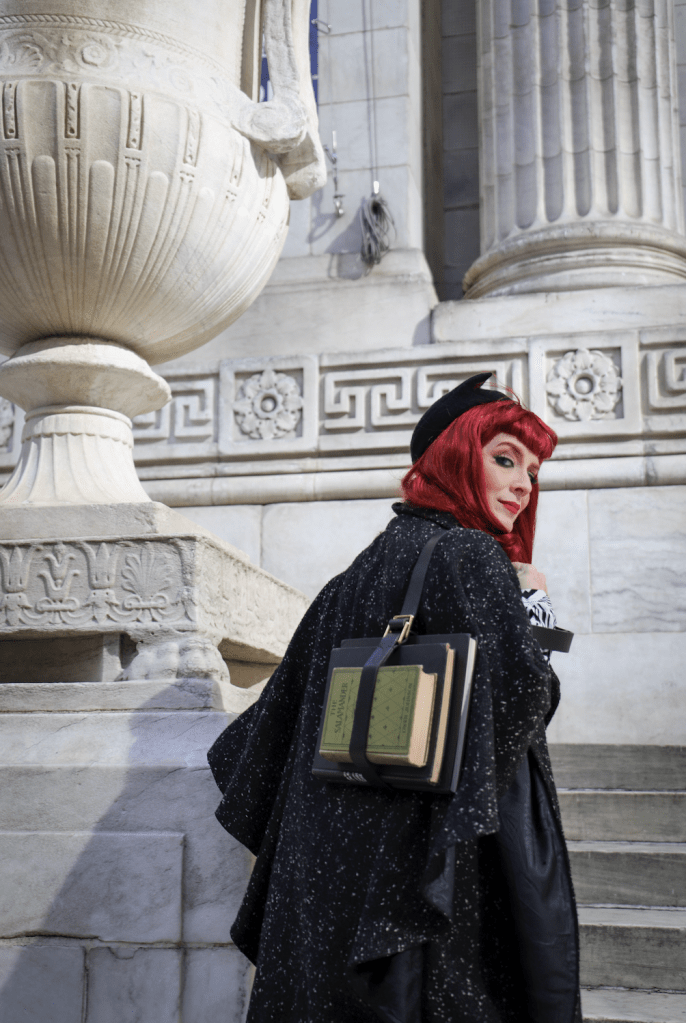

Ana Matronic talks her new podcast, Scissor Sisters’ reunion, and her friend Heklina. (Krys Fox)

Scissor Sisters’ singer Ana Matronic recently started a podcast, but for a minute, her fans weren’t thrilled.

Good Time Sallies, in which Matronic profiles marginalised women and “pleasure seekers” of the 20th century who had their lives ruptured by fascism in the wake of World War II, began production in 2021. It’s since evolved into “several long-term research and writing projects” which, as Matronic detailed in an Instagram statement last October, have prevented her from joining the Scissor Sisters’ reunion tour this May.

“Oh, yes!” Matronic says today of whether she’d ever rejoin the band, which went on hiatus after their fourth album, 2012’s Magic Hour. “Never say never. I’ve learned you can never fully ever close the door and nor should you. But at this point, I’ve been out of the band longer than I was in the band, and so my work has taken on a different medium.”

She pensively clutches her chin. “The thread that links it all is storytelling, and I was the storyteller of Scissor Sisters and the emotional engine, I suppose.”

We’re chatting via video call, she in London on one of the year’s first proper sunny spring days. It becomes clear why she dubs herself a storyteller, as our conversation stretches from grief to raving beneath a giant statue of an alien Virgin Mary. She’s a bewitching presence, a little like every gay student’s English teacher.

Finding out she sold crystals in the mall growing up makes perfect sense. Her once supremely coiffed, burnt orange fringe is swept to the side under a black-and-white chequered headband. She’s wearing a matching cardigan-blouse combo. It’s very retro, very glam, very Ana Matronic.

“I have a lot of information in this head that cannot be contained”

Matronic, born Ana Lynch in 1974, was very much the face of the chart-topping noughties glam-pop band, alongside leading man Jake Shears (Shears, Babydaddy and Del Marquis, are the ones touring). Yet as she details her new audio venture, it becomes clear she’s always viewed herself as student first, superstar second.

After Scissor Sisters, she hosted a BBC Radio 2 dance music show in the Sunday small hours, wrote a book about robots (she’s fascinated by them – hence the stage name), and as soon as our call wraps up, she’s off to the Leigh Bowery exhibition at the Tate Modern. “I have a lot of information in this head that cannot be contained,” she laughs, her eyes widening manically.

She’s a self-professed history nerd, with a particular affection for queer nightlife. The first two episodes of Good Time Sallies see her talk a mile a minute about the hidden legacy of Madame Spivy, a lesbian cabaret artist whose New York nightclub Spivy’s Roof was celebrating and embracing LGBTQ+ folk almost three decades before the Stonewall riots.

She wants nightlife to be treated as an art in the same vein as painting or sculpting. “Pleasure seekers are looked down upon a lot in society,” she says. She’s still very much part of the scene herself; she’s got her own annual DJ residency on Fire Island. “We don’t speak in the same terms of bartenders or go-go dancers as we do painters and the people who inspired them. I think we should.”

Matronic has lived in New York herself since the late nineties – “I just can’t quit her!” – where she met Shears at Knock-Off, a queer cabaret show she started. The band formed in 2000, and would spend 12 years bothering the charts with mammoth hits including “I Don’t Feel Like Dancin'” and “Take Your Mama”.

Their self-titled debut remains one of the best-selling records of the 21st century.

Shears recently expressed “resentment” at the group being labelled a “gay band” at their apex, which he felt made it easier for critics to “dismiss” them. Matronic addresses this today circuitously, suggesting that “music criticism has been run by white dudes who love rock and roll, and white dudes who love rock and roll tend to devalue things that gays and girls like” – like two of her other big loves, Eurovision and Drag Race.

“Chappell Roan… I love her. I think she’s fantastic”

She recognises there’s been a sea change in recent years, with the ascent of stars like Chappell Roan who – at least subconsciously – tapped into some of Scissor Sisters’ fruity bombast for songs like “Pink Pony Club” and “Femininomenon”.

“I am so happy that it is where it is. I want to see more queer artists. I want to see more queer artists of colour. I want to see more trans artists,” she says. “To hear and see somebody like Chappell Roan, who I think also is so right on with her values, she is taking her platform and understanding what she has and what she can do with it. It’s so great. I love her. I think she’s fantastic.”

Matronic’s infatuation with culture started aged 11, when her sister brought home a copy of The Cure’s The Head of the Door, and she watched queer sci-fi flick Liquid Sky, about an alien infiltrating Manhattan’s punk club scene in search of sex-induced endorphins (“..a very advanced film for an 11-year-old to see,” she admits). Her mother, a bohemian painter, and grandmother, would share their adoration of culture with her. “When I brought home a Prince record, my mom said, ‘Oh, he sounds like Little Richard.’ She put me in the car and took me to buy a Little Richard record.”

Her first time in a nightclub was aged 14 in her home city, Portland, Oregon. It was “an all ages queer nightclub that did not serve alcohol”, where music ranged from New Wave to Industrial Goth. “It was deeply queer and also extremely punk rock” – all guyliner and Doc Martins. “This was also [during] the AIDS crisis. I was getting involved with my friends who were demonstrating and involved in [queer activism groups] Act Up and Queer Nation and saying things like, ‘We are not gay as in happy, we are queer as in f**k you.’” She produces a wry smile. “That is a message that I still deeply identify with.”

Queerness consumed her upbringing. Matronic, who has been married to her husband Seth Kirby for 15 years, identifies as pansexual, and uses “she” and “they” pronouns (but prefers “she”).

She started her nightlife career as a drag performer at a burlesque show in Portland, before moving to an apartment in San Francisco with a queer friend. She knew the Californian city well: growing up, she’d often visit her father, who was gay, in the queer Castro neighbourhood he lived in. He died of AIDS-related complications when she was just 15. Her grandmother died exactly a month later.

“Not even a week after I moved to San Francisco, I went to [legendary queer club] T Shack, and the next Tuesday I was on stage performing. I did Nina Hagen.” She cackles at the memory. At T Shack, where she performed every Tuesday for three years alongside drag star Peaches Christ, she met another drag icon who would go on to shape not only her life, but inadvertently the Scissor Sisters’ success: the outrageous, hilarious, pioneering San Fran legend, Heklina.

“Heklina and I were extremely close”

Heklina moved into Matronic’s apartment building, and the musician would help Heklina groom (or grime) her wigs. It was Heklina who first showed Matronic the wonders of New York nightlife, where she’d eventually move and launch the band. “Heklina and I were extremely close,” she recalls today. In April 2023, Heklina was found dead by Peaches Christ in an apartment in London, where the pair were performing. She was 55.

Matronic was understandably “shattered” by her friend’s death, which the Metropolitan Police has deemed “unexpected”. In February, the force apologised for its handling of the investigation; it took almost two years to issue an appeal to find three men believed to be at the flat before Heklina’s death, while Peaches claimed that every email she sent to those investigating went “unanswered for months”.

On 31 March, Matronic will join Peaches and other drag artists at a “Justice For Heklina” rally at the Met Police HQ in London, protesting against the force’s evidenced homophobia. She will address the crowd, telling them what Heklina and Steven Grygelko, the person behind the makeup, was like. She also wants justice.

“I want answers for her and our community and our family. Heklina was my family and I really wouldn’t be the person I am today [without her],” she says, her eyes getting dewy. She also wants her fans to know that without Heklina’s turn of phrase, “Filthy/Gorgeous” – the Scissor Sisters’ first top five UK hit, and first number one smash on the US Billboard dance chart – simply wouldn’t exist. By that merit, the band could’ve been snuffed out before even getting to work on their second album.

“Filthy meant you looked really good. Gorgeous meant you were looking absolutely rotten, and it was the best thing ever. Anytime you hear ‘Filthy/Gorgeous’, you are engaging in San Francisco drag lingo, and that is 100 per cent down to Heklina,” Matronic says, at her most stern. Look closely at the sexcapade music video, and you’ll spot Heklina in the crowd. “She used to call me up and she’d be like…” Matronic flicks her fingers into a telephone gesture and puts on her coarsest, loudest accent: “‘Call me back! I MADE you!’ and hang up.”

In a way, much of the work Matronic does is shaped by grief. I suggest that, for decades to come, people will probably make podcasts about her and Scissor Sisters’ impact on queer culture. Does she recognise her own influence? “Yes and no… yeah. I do see myself as part of it, for sure. Queer dance culture?

“Sadness and loss unites us”

“Absolutely,” she says. “It makes me feel so happy because my father grew up unable to express himself and unable to be honest about who he is, so I’m sad that he wasn’t here to see it. Of course, there is a great deal of living in his name and work in his name that I do.” She flutters her eyelashes again, batting away brewing tears. “I just turned 50 and 50 was his last birthday before he was taken by HIV/AIDS, so it is very poignant as well.”

I share my own experience of parental illness. “I’m so sorry,” she says warmly. “That sadness and loss unites us.” She delves into what queer clubs were like in the shadows of the AIDS crisis: there was safe sex education; free clinics; hotline numbers for shelters.

“The queer club wasn’t just a safe space for people to express themselves, it was also a community hub and a community centre,” she explains. “We have a lot of options with technology to connect with people, but there’s nothing like getting in a room and rubbing elbows.” She chuckles and sticks out her tongue: “…maybe more!”

Today, the climate for the LGBTQ+ community, particularly trans people, is “pretty bleak” she recognises. But she’s been here before, through the epidemic, through Trump round one. “The best thing to do is to get together, because when we get together, we are unstoppable,” she urges, be that through action on the streets or getting action on the dancefloor. It takes her back to Spivy’s club in the 1940s, where queer women could enjoy dinner, drinks and a show, shutting the doors on the world imploding outside.

“I hope that people will listen to Good Time Sallies, learn about Madam Spivy, and call up their most cantankerous lesbian friend and take them out for a night on the town,” she hoots, eyes wide still, picking up a cup of tea. You best believe you’ll see Matronic there, either on the decks, behind a mic, or sweating alongside you in the crowd.

Good Time Sallies is available on all podcast streaming platforms.

Share your thoughts! Let us know in the comments below, and remember to keep the conversation respectful.

How did this story make you feel?