Laos—a landlocked country wedged between China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, and Burma—is suffering an exodus of human capital, as organized crime fueled by Chinese money lures graduates away with paychecks that dwarf local wages.

Students who master the Mandarin language at the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) soft-power project, the Confucius Institute, hosted by the National University of Laos (NUOL), are sliding straight into jobs at Chinese-run telecom-fraud centers, says Liu Ao, a Chinese national who spent two years at the campus’s international development graduate program.

“Most end up in the Golden Triangle doing telecom fraud. It’s an open secret,” Liu told The Epoch Times, referencing the mountainous so-called Golden Triangle region that straddles northeastern Burma, northwestern Thailand and northern Laos, once synonymous with opium production, and now increasingly a hub of transitional cyber scams.

Liu’s experiences and insights are corroborated by International Crisis Group field reports, U.S. sanctions files, and Interpol alerts.

According to those accounts, after years of pushing its soft power influence in Laos, through its Belt-and-Road infrastructure (BRI) loans and Confucius Institutes, the CCP has succeeded in having Laotians deepen their financial ties and dependence on China.

This influence has now extended to many Laotian graduates, who are opting to leave the capital in Vientiane for jobs in the now-infamous Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone (GTSEZ) on the northwestern border, drawn by paychecks their home economy cannot match.

Demand for Mandarin in Laos has soared since its ruling communist government began allowing Chinese investments, largely unregulated, into the country.

Applications for its bachelor’s program nearly tripled between 2021 and 2023, even as overall university enrollment fell; in August 2023, 2,330 of 17,198 NUOL students applied to study Chinese, while 1,886 chose English, RFA reported, citing university data.

Laotian officials openly link the boom to the influx of Chinese companies that need bilingual staff.

Yet those skills travel north far more often than they land a desk job in Vientiane.

Liu enrolled at NUOL in 2022 for a master’s in international development and recalls teachers quietly admitting where many of the institute’s graduates go.

Liu said scam bosses scour Laos for Mandarin speakers steeped in Chinese internet culture to pose as investment advisers, customer-service reps, or long-distance love interests to target victims in mainland China and Chinese-speaking communities.

“That’s exactly the profile NUOL’s Confucius Institute produces,” he said of the institute’s graduates.

Pay is the bait. An entry-level graduate job in Laos’ capital earns barely 1,000 yuan (about $140) a month; a rookie scammer inside GTSEZ can pocket 10,000 yuan (about $1,400) a month—ten times as much, Liu said.

“It’s the only ladder up,” Liu added, “and they learn Chinese only to con Chinese—it’s beyond ironic.”

A Kingdom of Scams

The GTSEZ was cut out of Laos’ northwestern Bokeo Province in 2007 in an agreement between the Laotian authorities and a China-based company for spurring tourism and economic development with the creation of an international casino and entertainment complex, with supporting infrastructure.Laos granted Chinese casino tycoon Zhao Wei and his Hong Kong-registered Kings Romans Group a 99-year lease on a 10,000-hectare tract, of which 3,000 hectares had duty-free status and autonomy for the company to wield its own security and administrative rules.

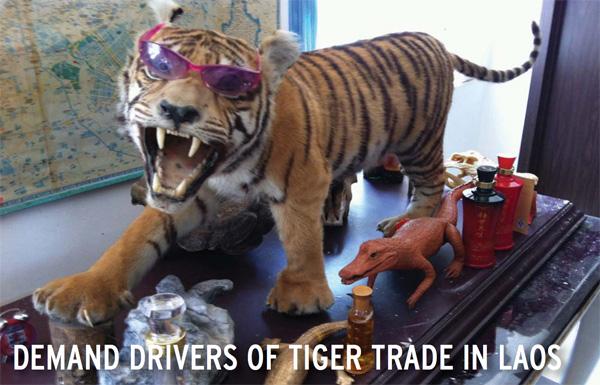

The zone has since transformed into a criminal hub for scam operations, illegal drug and arms trade, and even suspected activity by Chinese police on Laotian soil.

In addition, the scam compounds often adjoined Beijing-financed railways and casinos pitched to Chinese tourists.

“What began as a regional crime threat has become a global human trafficking crisis,” Interpol Secretary General Jurgen Stock said at the time.

An August 2024 raid by Lao officers and Chinese security agents detained 771 suspects and ordered scam compounds to shut within two weeks—the toughest action Vientiane had taken in 17 years, though investigators concede the operations had already raked in billions.

By mid-2024, mainland Chinese police said they had cracked 294,000 telecom-fraud cases in that year alone, many linked to compounds in Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia, triggering a storm of social-media anger in China.

Negative headlines were tarnishing China’s “win-win” narrative for its BRI projects.

Sending officers to the GTSEZ let Beijing show it was “protecting the people” even though this was beyond its borders, while streamlining the identification and swift repatriation of Chinese suspects.

Soft Power With a Hard Edge

A mountain of debt explains why Laos continues to tolerate the GTSEZ Chinese lease.

Chinese fingerprints even appear in policing. ASEAN meetings as far back as 2005 show Laotian patrol cars emblazoned with the words, “Granted by The People’s Republic of China.”

Beyond the GTSEZ, Chinese state-owned enterprises dominate Vientiane’s skyline with rail lines, malls, and luxury towers, while many Lao residents live in wooden shacks on the city’s outskirts.

“Wages are so low locals can’t afford these projects; they just watch Chinese firms rake in money while seeing no benefit themselves,” Liu said.

The Chinese influence reaches deeper.

In 2023, Laotian police detained Chinese human-rights lawyer Lu Siwei at Beijing’s request as he prepared to board a train to Thailand at Laos’ Thanaleng railway station near the Lao–Thai border. Despite protests from the United Nations and rights groups, the dissident Chinese national was extradited back to China.

“People say it’s easier for Beijing to have someone killed here than at home,” Liu added, citing loose gun laws and business-related shootings.

He believes data from Chinese-owned firms in Laos feeds straight to Chinese police, citing his conversation with a Lao deputy health minister. This would have helped Chinese authorities track down lawyer Lu.

As a Chinese national, Liu said he has also felt the reach of Beijing’s transnational repression of the Chinese people’s political freedoms.

While in Laos, he participated in activities run by a Los Angeles-based anti-CCP group and shared an apartment with like-minded students. After he moved out, Laotian police raided the flat, claimed it was a “prostitution” den, and detained the landlord.

“It was a student neighborhood—we don’t buy that excuse,” he said.

For Liu, the CCP’s Confucius Institute, Chinese state firms, and the special economic zone have merged into a crime engine. The costs, he warns, fall on both Laotian society and Chinese national victims ensnared by the scams that begin in a university classroom and end in a Golden Triangle compound.